Calendar kinks

Burkard Polster and Marty Ross

The Age, 28 April 2014

One of the fiddly little jobs of a lecturer is to timetable the subjects he is to teach. The plan is always just to copy the previous year's timetable and invariably the plan fails dismally. Alas, there is no consistency to when terms start and end, nor to how public holidays will fit in. Easter will do its crazy Easter thing, and so on. It is not just annoying for lecturers and students; these date games befuddle everyone.

Wouldn't it be convenient to have a perpetual calendar, one that simply repeats itself like a clock? Then any special occasion, such as last Friday's Anzac Day, would always be on the same day of the week. School terms and holidays could always start and end on the same dates, and on and on. No more guessing of dates and no more juggling to fit in with the vagaries of each new year's calendar.

Of course such a calendar must be an impossibility. We wouldn't have suffered through millennia of calendric randomness if there were an easy solution, right?

Wrong. There are a number of simple and clever perpetual calendars, any of which would be a vast improvement on our current clunky one. So why are they so secret and why can't the World agree to adopt one of them?

Any calendar begins with the observation that a year, the time it takes the Earth to complete its trip around the Sun, is about 365 days. So, we might simply number the days from 1 to 365 and be done with it.

Very simple, if not very useful. We would also hope to divide our year into something like weeks or months or seasons, as we currently do. That's where we can be easily led astray.

If we want to stick with tradition and declare a week to be seven days it seems we're doomed to a calendar that changes each year. 7 does not go evenly into 365 and that's that. Months, traditionally based upon the Moon's orbit of the Earth, are even trickier. The Moon's trip takes about 29 1/2 days. We can crib a bit and go for either 29-day or 30-day months but neither goes neatly into 365.

Perhaps we can rethink some of this. After all, there is nothing God-given about a 7-day week. Well, actually, the 7-day week is God-given. However that is a pretty poor argument for a modern world. And there is hardly a strong call for lunar months, except amongst werewolves.

If we're happy to ditch the traditions then we're left with figuring out how to divide 365 into smaller, equal units. However 365 = 5 x 73, and 5 and 73 are both prime numbers. That means our only options are five "months" of 73 days each, or seventy-three "weeks" of 5 days each. Neither is very appealing.

Let's cheat: if we remove a day then we're left with 364 = 13 x 28 days, which is much more promising. We can then have thirteen months of 28 days, and each month can be divided into four weeks of 7 days.

This calendar resembles our existing one but is much more regular. Not only would every year start on the same day of the week, so would every month. It could also have the spooky bonus of providing us with a Friday 13th every month. (Unfortunately, Easter would probably continue to do its crazy Easter thing.)

That'd be great but what about the missing, 365th day? That's easy: we just chuck it in at the end of the year as an extra holiday, with no day of the week assigned to it. We suggest that it be named QED Cat Day.

Of course there's that whole leap year thing, where we account for a year being a bit longer than 365 days, ensuring that our calendar stays in synch with the seasons. That can be handled just as it is now, adding an extra leap day to a year as required (more or less once every four years). Again, the trick is simply to not assign a day of the week to this extra day.

This is a promising calendar but admittedly having thirteen months in a year could be considered unsatisfactory. It would be convenient to have the calendar mark off seasons of equal length and 13 is another annoying prime number. Luckily, there is a simple alternative that will work.

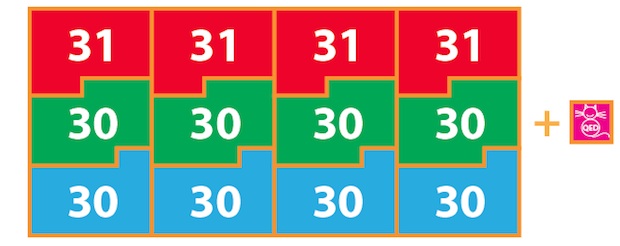

We can factorise 364 = 4 x 91, which means we could have four seasons of 91 days each. Then each season could consist of three months of 31, 30 and 30 days. That would be very similar to our current calendar of twelve months, with QED Cat Day again included to complete the year.

These are great ideas but QED Cat doesn't deserve (and is unlikely to get) all the credit. Such calendars have been around a while and have already received significant attention. The idea of a 13-month calendar dates back to the 18th century and our version above, known as the International Fixed Calendar, was seriously considered for adoption by the League of Nations in 1923. The perpetual 12-month calendar above, known as the World Calendar, was considered by the United Nations in 1955.

Why weren't the calendars adopted? It seems that God will giveth clumsy calendars but won't take them away. The failure of these calendars to win approval was mainly due to the opposition of religious fundamentalists. Though weeks would have still consisted of the traditional seven days, that one extra QED Cat Day was deemed to violate the "rest on the seventh day" thing. Sheesh.

These days calendar reform is less of a concern. We all have computers to help us cope with the consequences of pious obstinance. Still, a sensible calendar would be pleasing and is well overdue. And, with the steady waning of religion's intellectual (and moral) authority, who knows what the future will bring?

Actually, what the future will definitely bring is a year of 364 days: the years are slowly but inevitably getting shorter and the days are getting longer. In a few million years or so, the year will have lost a day and finally it'll be possible to please everyone. For a while. Until we lose another day, and we have to begin the haggling all over again.

Burkard Polster teaches mathematics at Monash and is the university's resident mathemagician, mathematical juggler, origami expert, bubble-master, shoelace charmer, and Count von Count impersonator.

Marty Ross is a mathematical nomad. His hobby is helping Barbie smash calculators and iPads with a hammer.

Copyright 2004-∞ ![]() All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.