Footy's pointless point

by Burkard Polster and Marty Ross

The Age, 18 March 2013

We’ll miss the cricket. It’s provided some fantastic summer entertainment, with the highlight being the dumping of four test players for failing to complete their homework. We had always thought of cricket as a gentleman’s pastime, but it seems that it’s now a game for petty schoolmasters.

Now, and not a day too soon, it’s footy time. The 2013 AFL season starts on Friday, and this week-end offers a non-stop feast of … two matches.

Well at least the slow start leaves us time to fine-tune our UltimateMegaFantasy DreamTeam. We’ll be poring over all the numbers: the goals kicked, frees against, inside 50s, and on and on.

Of course not all numbers are equally important, and one numerical aspect of the AFL turns out to be surprisingly irrelevant: the scoring of behinds.

We suspect most of our readers have some familiarity with Aussie rules scoring, since it’s one of the requirements for Victorian citizenship. (This is almost not a joke.) However, for the benefit of those just off the boat, here’s a quick review.

A goal in the AFL is worth 6 points, and a behind (a “touched goal”, or kicking the ball through the posts either side of the main goal area) is worth 1 point. The total points scored by a team is then the sum of the points from their goals and behinds, and whichever team scores the most points wins.

That’s simple enough but why not make it even simpler? Why not just score goals alone?

One plausible answer is that including behinds in the score should lower the frequency of drawn matches. We’re not sure why a draw is such an undesirable outcome but this was exactly the argument made in 1897; that’s when behinds were first included in the scoring, in the newly formed Victorian Football League. However, the big problem which behinds were supposed to remedy was, and is, really not so big.

In the 1897 VFL season there was an average of just over 10 goals per game. So it was reasonable to expect that including behinds would have avoided a significant number of “draws”. It didn’t happen.

In only 4 of the 62 matches in the 1897 season did the two teams finish with the same number of goals. Moreover, one of those matches was actually a draw, and so counting behinds made no difference. So, for all that scoring and all that extra waving of the white flags, behinds acted as the desired tiebreaker in less than 5% of matches. Hardly worth the bother.

In the modern era teams are more equally matched but goals are more plentiful. The result is that behinds still seldom function as tiebreakers. It occurred in only 8 of last year’s 207 matches, less than 4% of the total.

Of course, whatever the original intent, behinds don’t only function as tiebreakers: they can actually switch the winner and loser. For example, in Round 19 last year the mighty(ish) Saints lost to evil Collingwood, 13.7 (85) to 12.19 (91). The Saints’ extra goal was outweighed by the Pies’ extra behinds.

So perhaps behinds matter after all. Again, not so much. Last year, beyond the 8 matches mentioned previously, only 6 matches were won on the basis of extra behinds.

So as it stands there is not much point to including behinds in the score. What should the AFL do about it?

Intuitively, and the evidence bears it out, awarding a single point for a behind is simply too low in comparison to the 6 points for a goal. So we might try making a behind worth 2 points or, equivalently, awarding only three points for a goal.

Perhaps that’s too extreme, and so one might consider a goal being worth 4 or 5 points. The point is that there’s nothing magical about awarding 6 points for a goal (even if 6 is a perfect number). In any case, it would seem to make sense for the AFL to consider the desirable balance between goals and behinds.

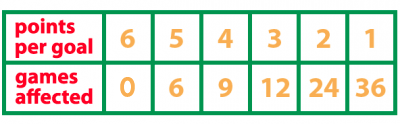

The table below indicates the effect that changing the value of a goal would have had on the 2012 season.

The table suggests that unless a goal is valued at just 1 or 2 points, which would dramatically affect the way the game is played, behinds still won’t matter all that often. It seems that a reasonable conclusion is to give up on behinds altogether.

However there’s one piece of evidence we’ve overlooked: the 1966 Grand Final. It was in that game that Barry Breen’s behind with a minute to go gave the mighty (no ish) Saints their 1 point win over the evil Pies.

And that demonstrates the fundamental flaw in our analysis. In the end football is not about being reasonable; it’s about beating Collingwood.

Burkard Polster teaches mathematics at Monash and is the university's resident mathemagician, mathematical juggler, origami expert, bubble-master, shoelace charmer, and Count von Count impersonator.

Marty Ross is a mathematical nomad. His hobby is smashing calculators with a hammer.

Copyright 2004-∞ ![]() All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.