Tally up the votes that count

By Burkard Polster and Marty Ross

The Age, 29 October 2007

Now that the Federal Election is upon us, we can seriously ponder who to vote for. That may be depressing, so let’s ponder something else: what about our voting system? Are our individual votes combined to choose a worthy winner? As we shall see, this question is even more depressing: the answer is a resounding and necessary “No”!

In any big election, the population is divided into electorates; for each electorate there are one or more winners, and then those winners are somehow used to calculate the overall winner. We won’t delve into this, though there are of course many contentious issues with the structure of electorate voting. The point is, there are even more fundamental problems: even when the election consists of choosing a single winner in a single electorate, there is no mathematically satisfactory voting system.

Let us first imagine an election with only two candidates, Dopey and Grumpy. In this case, there is no controversy: whoever gets more votes is the winner. The problems begin when a third candidate enters the race. It may still be the case that one candidate receives more than 50% of the votes, and then we can declare them the winner. But what if no candidate gets that many votes?

The simplest multi-candidate system is plurality voting: the candidate with the most votes is the winner. For example, Grumpy would win with 40% of the votes, if Dopey and a third candidate, Sneezy, each received 30%. Though commonly used, the potential drawback of plurality voting is obvious: Dopey and Sneezy may well be likeminded candidates, and so it may be that their combined 60% of supporters would be quite happy with either as winner, whilst detesting Grumpy. And this is not merely a theoretical danger: it is very likely that George Bush won the 2000 American Presidential Election only because the anti-Bush votes were split between Al Gore and Ralph Nader.

Is there a better alternative? In the 18th Century the Marquis de Condorcet came up with a possibility. Condorcet suggested that we simply take all the candidates two at a time: then the candidate who wins all of their head-to-head races is the winner. For example, with the assumptions above, either Dopey or Sneezy would win 60-40 against Grumpy. So, whoever then won between Dopey and Sneezy would be declared the Condorcet winner.

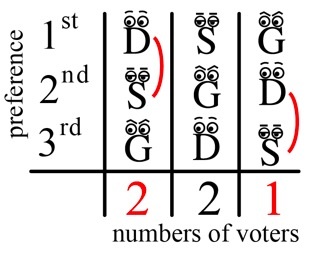

The Condorcet system is very simple, but Condorcet realized the critical flaw: there may not actually be a Condorcet winner! For example, suppose there are 5 voters, and their preferences are as follows:

Then, as indicated in the table, Dopey beats Sneezy 3-2. Similarly, Sneezy beats Grumpy, but then Grumpy beats Dopey! So who is the Condorcet winner? No one!

The Australian approach to voting is the Hare Preferential System. In this system we look at the voters’ first preferences, and the candidate with the lowest number of first preferences is eliminated. The eliminated votes are then redistributed to the second preferences, and so on, until only one candidate is left. So, in the previous example, Grumpy is eliminated first, giving one extra vote to Dopey, who therefore wins 3-2 against Sneezy.

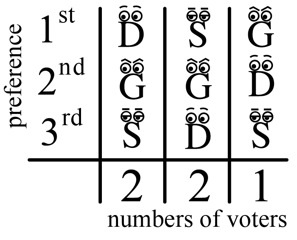

The Hare system is fairly natural and always results in a winner (excepting ties), but Condorcet voting shows that this system has its own problems. For example, suppose the 2 voters in the first column switch their 2nd and 3rd preferences, giving the following:

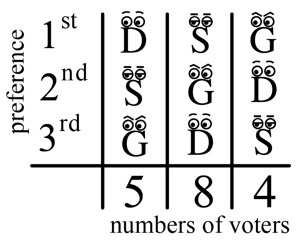

This doesn’t change the fact that Dopey is the Hare winner. But notice that Grumpy is now a Condorcet winner! That should make us pause: why should we be happy about declaring Dopey the overall winner if he cannot even win a straight race against Grumpy? But even stranger things can happen. Imagine we had 17 voters, with the following preferences:

Then Dopey is the Hare winner, 9-8 over Sneezy. But notice that Sneezy could have been the Hare winner, if only fewer people had voted for him!

Imagine if 2 of those who voted for Sneezy had instead joined the 4 who voted for Grumpy. Then the numbers of votes in each column would now be 5, 6 and 6. Dopey would immediately be eliminated, and Dopey’s second preferences would have ensured Sneezy won 11-6 against Grumpy.

So the Hare system is very far from perfect. Can we do better? Not really. There are subtler systems, which take voters’ preferences more accurately into account. But, in 1950, the mathematical economist Kenneth Arrow proved that essentially any voting system will have paradoxes such as the above: there will always be some voting scenario which makes the system look silly.

One obvious question remains: is this all theoretical, or can these voting paradoxes really occur in Australian voting? The answer is, definitely the latter. Here is a possible example, the Senate race in South Australia, in the 2004 Federal Election. For precise numbers, see Antony Green’s wonderful election material on the ABC website.

With 5 parties left in a tight race, the Australian Democrats were eliminated. The Australian Greens were coming second, but a preference deal between the Democrats and the Family First Party temporarily kept Family First in the race, and doomed the Greens. The seat was eventually won by the Australian Labor Party.

Was there anything the Greens could have done? In practice, no. But with hindsight they may easily have won. Similar to the above example, the Greens just needed to have had about 8000 fewer people vote for them!

If 8000 Greens voters had instead voted for the Democrats, then the Democrats would have survived and Family First would have been eliminated. The preference deal probably would have next eliminated the Liberal Party, and it is possible that the Greens would have then won the subsequent 3-way race. And the moral of this is … well, we don’t know what the moral is. Except that voting is weird.

Copyright 2004-∞ ![]() All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.