Do women have fewer teeth than men?

by Burkard Polster and Marty Ross

The Age, 14 March 2011

Our dentist assures us that the answer is no, that men and women naturally have the same number of teeth. And of course we hardly need a dentist to confirm this: we could simply gather some tolerant, open-mouthed friends and get counting.

It is therefore surprising that the great philosopher Aristotle claimed that yes, indeed, women have fewer teeth than men. This neatly demonstrates that brilliant philosophers can engage in less than brilliant science.

Actually, some modern philosophers have sought to defend Aristotle against the charge of sloppy science. Nutrition and dental care in ancient Greece were not that great, especially among women. So, perhaps women of the time did tend to have fewer teeth. Perhaps. However, it wouldn’t have been that difficult for Aristotle to have also counted the gaps between the teeth.

If Aristotle has a possible defense for his toothy error, he committed another declarative blunder, with no such defense. Aristotle falsely claimed that tetrahedra could be used to fill space, without any gaps.

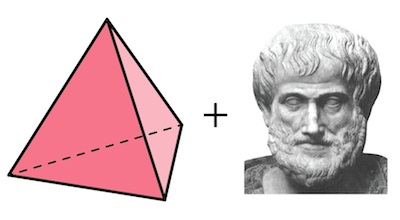

What’s a tetrahedron again? One of those things pictured above. The literal translation of the Greek is tetra = four and hedron = seats/sides. So, a tetrahedron is a shape with four sides, and it turns out these sides must be triangular. More precisely, most people use the word to mean a regular tetrahedron, one with all sides equilateral triangles.

A regular tetrahedron is one of the five Platonic solids, named after Plato, Aristotle’s teacher. The simplest of these Platonic solids is the cube. Of course, it is very easy to fill all of space with cubes. Aristotle’s false claim was that the same can be accomplished with regular tetrahedra.

We can sort of understand the teeth business, but how did Aristotle get Plato’s tetrahedron so wrong? Weren’t the ancient Greeks the original masters of geometry and mathematical proof? How difficult would it have been to stick a few tetrahedra together and check it out?

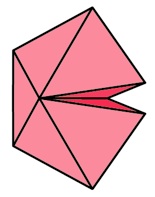

A very accurate model of a tetrahedron can be built using six straws of equal length and some thread. Experimenting with a few of these models, you can quickly convince yourself that any attempt at packing space will leave definite gaps. For example, arranging five tetrahedra around a common edge creates a wedge gap as pictured.

That is compelling evidence, though it doesn’t amount to a proof. However, it is not too difficult to juggle a few triangles, to come up with an airtight mathematical proof that a packing with regular tetrahedra is impossible.

How did Aristotle come to make this totally false claim? Recently, we stumbled across a possible clue, in a Lebanese shop in Brunswick. Perhaps Aristotle drank his orange juice from tetrapacks!

A commercial tetrapack is a tetrahedron, although not a regular one. And, the way they are packed in boxes in the shops suggests that tetrapacks might be able to pack space.

Actually, commercial tetrapacks are not the correct shape to pack space, at least not without a lot of squeezing. However, we can alter the dimensions to make mathematically perfect tetrapacks: a perfect tetrapack is constructed from four isosceles triangles, each triangle having edges in proportion 2:√3:√3. And, perfect tetrapacks can indeed be used to pack space, without any gaps or squeezing. Beautiful!

So, perhaps Aristotle was right after all. In fact, Aristotle’s writing is ambiguous, and it is arguable that he was referring to non-regular tetrahedra. However, in context it seems very unlikely. In fact, for more than a thousand years after Aristotle, people believed that regular tetrahedra could pack space. Finally, in the 15th Century, the German mathematician Regiomontanus actually bothered to check.

More likely, Aristotle simply had a bad day. We can imagine him, trying to enjoy his morning juice from a Platonic tetrapack. He’s pondering, thinking that these regular tetrahedra might stack nicely. But, he’s distracted by his nagging wife, who is stubbornly claiming that she has the same number of teeth as him. So, he leaves it to his wife, instructing her to go stack the regular tetrapacks in the pantry and forgets all about it. Then, a grumpy Aristotle saunters off, to go do some philosophy with Plato.

Puzzle to Ponder: The following images demonstrate how a tetrapack can be constructed. First, a rectangle is rolled up into a cylinder. Then, opposite ends are glued together, into two edges at right angles.

A regular tetrahedron can be constructed in this way, as long as you choose the initial rectangle to be of just the right proportions. What are these proportions?

Burkard Polster teaches mathematics at Monash and is the university's resident mathemagician, mathematical juggler, origami expert, bubble-master, shoelace charmer, and Count von Count impersonator.

Marty Ross is a mathematical nomad. His hobby is smashing calculators with a hammer.

Copyright 2004-∞ ![]() All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.