Poet of the Universe

by Burkard Polster and Marty Ross

The Age, 6 February 2012

Welcome back, for the sixth year of Maths Masters. We’re very grateful for the continued interest that our columns have received.

Again this year, we hope to write about some beautiful and little-known mathematics, and to explain more familiar maths that tends to confuse. And yes, we’ll probably wind up whacking a windmill or two. However, we’ve chosen to begin the year by honoring a very special mathematician.

In the 1980s, one of your maths masters was lucky enough to be invited to study at Stanford University. Soon after arriving, he met a mathematician who looked remarkably like Groucho Marx, complete with stooped walk, and a nasal, jokey manner.

Robert Osserman turned out to be almost nothing like Groucho. Bob definitely had a great sense of humour, but he was also gentle and generous. As it happened, your maths master began researching what are known as minimal surfaces (which are a mathematical idealization of soap films), a field in which Bob was an expert. Your maths master found himself asking Bob question after question. He read Osserman’s excellent (technical) introduction to minimal surfaces, many times over.

None of this is exceptional, merely indicative of an accomplished scholar and dedicated teacher. But then an opportunity arose.

As do most American universities, Stanford encourages undergrads to at least have some breadth in their studies. So, science students must read and write upon at least a few great books, and arts students are required to study a little maths and science.

University subjects are typically ill-suited to outsider students, so it is common for American universities to offer specialised “breadth subjects”. Bob Osserman, together with Sandy Fetter (physics) and Jim Adams (sociology) introduced such a year-long subject at Stanford: The Nature of Mathematics, Science and Technology. Your maths master was lucky enough to be one of the two tutors.

It was a terrific subject, with the three lecturers perfectly complementing each other: Bob introduced the abstract mathematical ideas; Sandy demonstrated how these ideas could be used to model the physical world; and Jim described the often circuitous path from the physics to technological breakthrough. This was gently and engagingly presented to a hundred nervous arts students, most of whom were ready to flee at the first appearance of an equation.

Your maths master is undoubtedly biased, but he found Bob Osserman’s presentations particularly enjoyable and insightful. Bob presented mathematics as a collection of ideas, and as the history of the mathematicians who struggled, not always successfully, to untangle those ideas.

Bob used the arts, and music in particular, to motivate the mathematics. He began with the Pythagorean theory of harmony, based upon simple ratios of string lengths: 2/1 and 3/2, and so on. Bob then demonstrated how that simple idea leads to more complicated ratios, and finally, almost in contradiction, to irrational numbers. This fascinating history also included a guest appearance by Vincenzo Galilei, the father of his much more famous son.

Bob, Sandy and Jim had planned to write a textbook for the subject but unfortunately it never eventuated. However, Bob did write Poetry of the Universe, a wonderful book intended for the general public.

Poetry of the Universe tells the history of the mathematical exploration of the Universe. Osserman begins the story in 240 BC, with the Alexandrian mathematician Eratosthenes and his stunningly simple calculation of the size of the Earth.

Eratosthenes knew that almost due South of Alexandria was the city of Syene, with a notable feature: at noon on the summer solstice, the Sun is directly overhead. Eratosthenes then measured that in Alexandria at that same time, the Sun makes an angle with the vertical of a little over 7 degrees, about 1/50 the way around a circle. From this, Eratosthenes deduced that the circumference of the Earth must be about 50 times the distance from Syene to Alexandria. That distance (in modern units) is about 800 kilometers, leading to a remarkably accurate estimate of the Earth’s circumference of about 40,000 kilometers.

Poetry of the Universe takes the story right up to the present day exploration of the shape of the Universe. Along the way there is wonderful history and fascinating digressions, perhaps the most fascinating of which is the story of Dante’s universe.

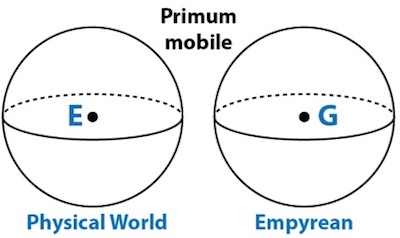

In Paradiso, the 14th Century poet Dante described the universe as consisting of two spheres. The first sphere is our physical world, with the Earth at its centre, and the outer layer of this sphere is the primum mobile. The second, heavenly sphere is the Empyrean, inhabited by the angels and with a godly point of light at its centre.

What is fascinating is that the primum mobile, the outer layer of the physical world, is simultaneously the outer layer of the Empyrean. This may be very difficult to imagine, but modern mathematicians know Dante’s universe very well.

As Osserman explains, Dante has perfectly described his universe as a hypersphere. Analogous to the borderless 2-dimensional surface of the Earth, a hypersphere is a borderless 3-dimensional world. It is possible that our Universe is a hypersphere, and the hypersphere is the central character of the famous Poincaré Conjecture.

In later years, Osserman was Special Projects Director of MSRI, one of the World’s most prestigious and successful mathematical institutes. In this role, Bob became much more involved in presenting mathematics to the wider community. He engaged in public conversation with such disparate artists as actor Alan Alda and pianist Christopher Taylor (both events being viewable online), comedian Steve Martin, composer Philip Glass and playwright Tom Stoppard. Bob Osserman recognised mathematics as an art, and he helped many others to see it that way.

Robert Osserman died at his home last November, at the age of 84. Your maths masters will spend the year trying to live up to the brilliant, beautiful example set by this wonderful man.

Burkard Polster teaches mathematics at Monash and is the university's resident mathemagician, mathematical juggler, origami expert, bubble-master, shoelace charmer, and Count von Count impersonator.

Marty Ross is a mathematical nomad. His hobby is smashing calculators with a hammer.

Copyright 2004-∞ ![]() All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.